Abandoning stamp can make DMEK better

S- or F-stamping donor tissue for Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty is widely practiced to guard against DMEK’s most embarrassing potential complication: accidental upside-down graft implantation.

These orientation marks are so common, in fact, that many DMEK surgeons have never even attempted the operation without them. However, the originally described DMEK technique was stamp-free, and that is still the way the operation is performed today at the Netherlands Institute for Innovative Ocular Surgery, where DMEK was invented. So, rather than a necessary feature, tissue stamps might be more appropriately regarded as “accessories,” with definite yet unmentioned drawbacks.

Admittedly, a certain emotional sense of security accompanies the use of stamped tissue. It feels like the safe thing to do. And if applied by the eye bank, it also requires no extra time, effort or expense. Finally, when not using stamps, the inevitable occurrence of an upside-down graft is so chastening and humiliating that it is enough to send any reasonable person searching for a “never again” solution.

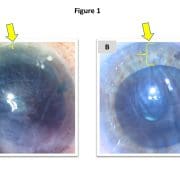

But, in practice, the stamp is just not that useful. The DMEK graft is almost always injected as a scroll, then opened and manipulated, even before the stamp is remotely discernable (Figure 1). Consequently, the stamp has no role in the critical part of the surgery (unfolding the graft); it only offers a final check against mistakes. But even this function is often thwarted because, frequently, the stamp is only partially applied, such that half of the common “S” or “F” is missing, rendering it nearly impossible to read (Figure 2). The reason these stamps are often so poorly retained is that eye banks are typically tentative in applying them because the process (ie, stamping with a metallic instrument dipped in ink and alcohol) is unquestionably damaging, resulting in a circular swath of dead graft. These areas are additionally liable to local detachment and delayed corneal clearance (Figure 3), and the ink marks remain faintly visible for years after the surgery. As a result, the typical outcome is a poor stamp, useless for determining orientation but visible forever in the patient’s eye in a region of dead cells.

It is also worth remembering that upside-down graft implantation is rare, occurring in fewer than 5% of operations, even without the use of tissue stamps and even during initial learning curves. So, because the potential benefit is (at most) one out of 20 cases, that means 19 out of 20 cases can only be harmed by the application of the stamp, which destroys cells every single time.

Finally, one of the most personally satisfying elements of DMEK is the beauty and elegance of the operation, which is partially spoiled by an unseemly purple tattoo. Abandoning the stamp might not make the operation easier, but it does make it better, and if DMEK surgeons did not care about that, then they would not have switched over from Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty in the first place.

Reference:

Dirisamer M, et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.03.031.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!