Optimize DMEK graft size by preoperative recipient white-to-white measurement

From Healios

June 18, 2021

Recently, Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty has emerged as the preferred treatment for corneal endothelial dysfunction because it affords the best visual acuity with the lowest risk for various complications.

As the operation has grown more popular, various innovations to the technique have been introduced, including so-called “patient ready” DMEK, featuring “pre-stripped, stamped and stained” tissue. Despite the added convenience, “patient ready DMEK” necessitates the graft diameter to be specified in advance.

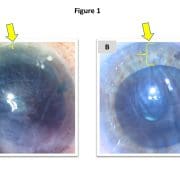

This obligation to specify in advance may result in a one-size-fits-all solution in which surgeons commonly use a standard/default graft size for (nearly) all patients. However, this default may occasionally produce undersized grafts, which inadequately treat the patient’s endothelial dysfunction (Figure 1a), or oversized grafts, which are more difficult to unfold and potentially prone to detachment (Figure 1b).

Rather than default sizes, it therefore may be desirable to tailor graft diameters for individual patients. However, this would require a method for reliably and conveniently measuring dimensions of the recipient eye before surgery. To this end, we propose a simple strategy — namely, using the preoperative horizontal corneal white-to-white (HWTW) provided by the Pentacam HR (Oculus).

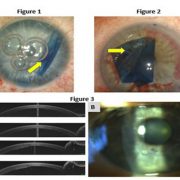

The Pentacam HR employs rotating Scheimpflug imaging to obtain 50 images of potentially 138,000 corneal locations, thereby generating data for the HWTW, which may be used to calculate the graft diameter necessary to cover the recipient posterior corneal surface.

Recently, we retrospectively evaluated our last 74 consecutive DMEK operations using “patient ready” tissue. Then, we compared our subjective surgical impression of the size of the graft (well sized vs. too big vs. too small) against the preoperative Pentacam HR measurements of HWTW to generate a graft sizing nomogram, which is presented in the table.

| Corneal HWTW (mm) | Graft diameter (mm) |

| < 10.5 | 7 |

| 10.5 to 10.75 | 7.25 |

| 10.75 to 11 | 7.5 |

| 11 to 11.25 | 7.75 |

| 11.25 to 11.5 | 8 |

| 11.5 to 11.75 | 8.25 |

| 11.75 to 12 | 8.5 |

| 12 to 12.25 | 8.75 |

| > 12.25 | 9 |

In our cohort of 74 eyes, the median HWTW was 11.65 mm, with 25% of eyes falling below 11.3 mm and 25% above 11.8 mm. For the median HWTW, a graft diameter of 8.25 mm appeared to be the optimal size (ie, could be unfolded easily and applied to the posterior cornea with a small peripheral rim of unstripped host Descemet’s membrane without overlapping). For eyes with HWTW higher or lower than the median value, the graft diameter should be adjusted, as described in the table.

Since implementing this nomogram, our incidence of mis-sized grafts has significantly decreased, resulting in easier and more enjoyable operations and fewer postoperative detachments. By incorporating more data points or additional patient anatomic parameters (for example, anterior chamber depth), it may be possible to further refine this nomogram and to provide detailed recommendations about graft sizing in difficult eyes (for example, eyes with very shallow or deep anterior chambers).